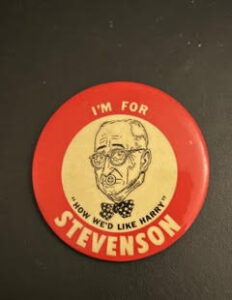

Harry Truman never thought much of Adlai Stevenson. The button shown here depicts a buttoned-up Harry Truman, showing support for Adlai Stevenson for President.

The Political Landscape of 1956

As the 1956 election approached, Republicans appeared vulnerable despite their popular incumbent. President Dwight “Ike” Eisenhower, while beloved for his World War II leadership, had struggled to maintain excitement in his role as Chief Executive. The GOP had suffered losses in the midterm elections, and Eisenhower’s 1955 heart attack raised questions about his health and political future. For Democrats, this seemed like an opportunity. Adlai Stevenson, who had unsuccessfully run against Eisenhower in 1952, believed the political winds had shifted in his favor and that he could succeed in a rematch against Ike. Truman, however, thought otherwise.

This eliminates the repetitive information about:

-

- Eisenhower’s WWII popularity vs. lackluster presidency

- Republican midterm losses

- Eisenhower’s 1955 heart attack

- Stevenson’s 1952 loss and 1956 optimism

While preserving the key detail about Truman’s opposition, which sets up the conflict that follows.

Truman’s Resistance

However, former President Harry Truman had different ideas. Far from enthusiastic about Stevenson’s second bid, Truman threw his considerable influence behind New York Governor W. Averell Harriman for the Democratic nomination. Truman’s opposition wasn’t subtle—he publicly branded Stevenson a “defeatist candidate,” creating a very public rift within the Democratic Party.

This harsh criticism infuriated Stevenson’s supporters and threatened to fracture the party at a crucial moment. The spectacle of a former Democratic president actively working against his party’s previous nominee created internal chaos that risked undermining any chance of defeating Eisenhower.

Stevenson’s Strategic Victory

Despite Truman’s opposition, Stevenson proved to be a skilled political operator. He successfully outmaneuvered both Truman and Harriman through a combination of well-timed endorsements and strategic promises. Most notably, Stevenson pledged to select a Southern running mate, a move that helped secure crucial regional support for his nomination.

Stevenson’s maneuvering was so effective that it not only secured him the nomination but also further marginalized Truman within his own party. The former president’s influence, once formidable, appeared to be waning as the Democratic Party moved beyond his era.

The Inevitable Outcome

In the end, Truman’s pessimistic assessment proved prophetic. Stevenson’s second campaign against Eisenhower resulted in an even more decisive defeat than his first attempt. The loss wasn’t close, validating Truman’s earlier warnings about Stevenson’s electoral prospects.

For Truman, this outcome provided bitter vindication. After Stevenson’s crushing defeat, the former president could finally utter the four words he had been waiting to say since the nomination: “I told you so!”

Historical Significance

This political button represents more than just campaign memorabilia—it captures a moment when the Democratic Party was caught between its past and future, embodied by the tension between the pragmatic Truman and the intellectual Stevenson. Their conflict highlighted the challenges facing Democrats as they struggled to find a winning formula against the popular Eisenhower and foreshadowed the party’s broader evolution in the years to come.

The former President cast his lot with New York Governor W. Averell Harriman as his pick for the Democratic nomination. Truman was very vocal about his support for Harriman, calling Stevenson a “defeatist candidate.” Stevenson’s people were incensed, and the Democrats looked like they might further fracture their party.

Ultimately, Stevenson was able to successfully outmaneuver Harriman with some well-timed endorsements and by promising to put a Southerner on the ticket. Stevenson successfully obtained his re-nomination, out-dueling both Truman and Harriman and further marginalizing the former President from his party. In the end, Stevenson lost once more to Ike. It wasn’t even close. And Truman was able to say the four words he’d been dying to say since Stevenson’s second nomination: “I told you so!”

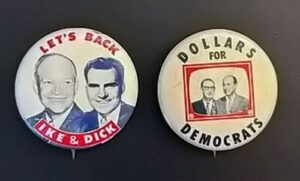

The 1950s belonged to the “Hero of D-Day,” General, then President Dwight David Eisenhower. “Ike” was unstoppable, first as head of the allied WWII armies and then as Commander in Chief during the beginning of the Cold War. However, a popular and academically minded Governor of Illinois, Adlai Stevenson, tried twice to unseat him. In 1956, still lagging in the polls, the Democrats held a televised fund-raising campaign. Donors received the button below as a “thank you.” Still, “Ike & Dick” bested Stevenson and Senator Estes Kefauver of Tennessee with a thorough thrashing. People happily “backed” Eisenhower and Nixon.

The 1950s belonged to the “Hero of D-Day,” General, then President Dwight David Eisenhower. “Ike” was unstoppable, first as head of the allied WWII armies and then as Commander in Chief during the beginning of the Cold War. However, a popular and academically minded Governor of Illinois, Adlai Stevenson, tried twice to unseat him. In 1956, still lagging in the polls, the Democrats held a televised fund-raising campaign. Donors received the button below as a “thank you.” Still, “Ike & Dick” bested Stevenson and Senator Estes Kefauver of Tennessee with a thorough thrashing. People happily “backed” Eisenhower and Nixon.